Book Review: The Legend of the Christmas Witch

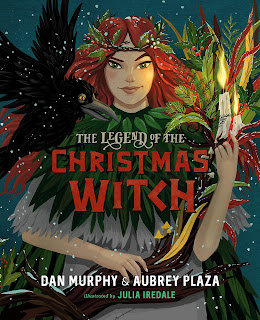

The Legend of the Christmas Witch

By Dan Murphy, Aubrey Plaza, and Julia Iredale

Not to be confused with the mangled English title of the movie, La Befana Vien di Notte, The Legend of the Christmas Witch is a 2021 children's book. The writing is credited to both Aubrey Plaza and Dan Murphy, but Plaza certainly seems to be the face of the project. I say "project" because this feels like something intended to expand, either through sequels or even by transitioning to some other media. Whether it does or not is anyone's guess: this may have some hurdles to climb, because...

This thing's going to piss off some people. Maybe a lot of people. I'll cut to the chase: this is a kid-friendly pagan, feminist deconstruction of Christmas and the patriarchy. It doesn't call out Christianity by name, but the message is hard to miss. On top of all that, the end of the book takes a turn that's pretty dark, or at least ambiguously so.

So, at the very least, I certainly respect Plaza's team for having the guts to go there. That said, is this actually any good? Well... that's hard to say. It isn't bad - the writing is fine, and the art is gorgeous - but at the same time I'm left with the question, "Who is this actually for?" While it's likely to find its way into the hands of families looking for a fun Christmas adventure, that's not really what it's selling.

Let's back up and talk premise and plot, though like a lot of children's literature, this is more idea than story. The main character is Kristtörn (drop the umlaut, and that translates to "holly," by the way), the twin sister of Kristoffer. The two children have magical abilities, are abandoned at a young age, and are raised by animals in an enchanted forest. So, basically we're kicking off with a twist on the opening to Life and Adventures of Santa Claus.

Kristoffer gets adopted by the Kringles and is more or less swept out of the narrative for a while. It's worth noting the reason he gets adopted and she doesn't is that he fails to alert the kind people who find him to the presence of his sister. Yeah... he doesn't exactly come off great in this narrative.

Kristtörn, on the other hand, is found and raised by Lutzelfrau, a kindly witch with a soft spot for the winter solstice who recognizes Kristtörn's innate magical abilities and wants to protect her. It's worth noting Lutzelfrau isn't invented for this book - she's one of several witches in European folklore associated with Christmas. And the fact most Americans still aren't aware that Christmas witches have been a concept for about as long as Saint Nicholas, is a large aspect of the subtext to this book.

See, Lutzelfrau and Kristtörn are in hiding. This book is set in a fairytale version of Earth where animals talk, but people here still burn witches. No sugar-coating, either - the book explicitly tells us this multiple times.

This is a problem, because Kristtörn isn't good at keeping a low profile. Eventually, she attracts attention, so Lutzelfrau sends her away for her own protection, promising her raven, Malachi, will keep an eye on her. By now, Kristtörn's quite a bit older, and with Malachi's help has been keeping track of her brother, who's already up at the North Pole. She sets off to find him, but takes a wrong turn and winds up marooned at the South Pole, where she's welcomed in by a group of talking penguins. She uses her magic to grow a tree and is eventually able to build a boat to return to Europe and look for her brother.

She spends several years trying to find him by leaving pieces of artwork on porches in the hopes he'll come across them on his Christmas Eve journey, but these instead attract the attention of angry mobs, convinced these are some sort of dark magic. She eventually does run into Kristoffer, but their reunion is cut short by the aforementioned mob carrying torches. Kristoffer takes off in his flying sleigh, and Kristtörn sails back to the South Pole, where her brother finds her again. She offers to help him in his Christmas mission, but he refuses, on the grounds she'd never be accepted. He takes off, abandoning her yet again.

She doesn't take this particularly well. Losing control of her temper, she vows to destroy Christmas in retaliation, then unintentionally unleashes her magic and accidentally shatters the ice beneath her feet. She and her penguin companions fall into the water below and are instantly frozen.

In an epilogue, we're told that she's still alive, asleep in the ice. And wouldn't you know it? The weather's changing, and ice is melting, so it's only a matter of time until she's free. Malachi, who's been narrating all along, wonders whether her kind heart will win out or if she'll carry through on her resolution to destroy her brother's holiday. It's ambiguous, and I kind of think we're meant to root for her to embrace her darker instincts (that was certainly my reaction).

There's a lot to admire here. The writers did their homework - I mentioned Lutzelfrau already, but there are quite a few other callouts to folklore through the book, including having Santa's companions as nisser. In addition, Kristtörn appears to be largely based on Befana. The gifts Kristtörn drops off while searching for her brother mirror those Befana delivers in her endless search for the Christ child (at least in the most famous version of that myth). Perhaps using the Kris Kringle moniker was a nod to this, as that name derives from the German for "Christ child." Or maybe I'm reading too much into this, who knows?

And I like that the narrative examines how feminine yuletide figures from folklore have been largely pushed out of the modern mythos (at least in America). In the book, Kristoffer comes off as privileged and somewhat obtuse. It's not so much that he's responsible for the misogynistic culture that threatens his sister, but he benefits from it and doesn't seem to address the problem. It's an interesting take and a fair criticism of the culture that Santa Claus coalesced in.

There are also obviously themes of Christianity supplanting paganism, as well as an undercurrent of environmentalism. The book doesn't quite say that the ice imprisoning Kristtörn is melting due to climate change, but it certainly implies it.

The problem with all that is... well... it's the talking penguins.

Okay, it's not actually the penguins, but they're a good illustration of why I think this book doesn't ultimately work. The penguins are cute, cartoonish, fun characters in the vein of Rankin/Bass. They're not alone, either - the book includes quite a few elements that come off as - frankly - childish. Obviously, this shouldn't be a problem in a children's book, but...

Is this a children's book? I mean, the themes are a bit weighty, the concepts are rooted in folklore, and the ending is at least ambiguously ominous. This isn't inappropriate for older kids, but I can't imagine young children reacting positively to the idea the protagonist might emerge from the ice and destroy Christmas in retaliation against those who abandoned and persecuted her. But older kids who might appreciate a subversive holiday story are going to be repelled by talking penguins, a heroine who lives at the South Pole, and the other silly stuff. There's a fine - and admittedly arbitrary - line between adult fantasy and children's stories, but it's one older kids tend to care about. Straddling that line is a recipe for trouble.

Overall, this is a neat book, and I'm glad I've got a copy. Julia Iredale's art is wonderful, and the concepts are fun. But while it's a neat idea, I find it hard to imagine this catching on. The narrative is too simplistic for teens, but the premise is both too dark and too cerebral for almost anyone younger.

That said, I'll be absolutely delighted if they convince Netflix to make a special without watering this down.

Comments

Post a Comment